I) Old immigration – historians in the past have used the designations “old immigration” and “new immigration” to distinguish between those people who came from northern and western Europe (the old immigrants) and southern and eastern Europe (the new immigrants). I purpose to use these old terms in new ways: to designate the old immigration as those immigrants who came before 1870; and those who came after. Technological innovations in travel, both sea and land, make this distinction viable because then we can highlight the real difference between immigrants, those who came to establish new homes, and those who came to earn enough money to improve their old homes.

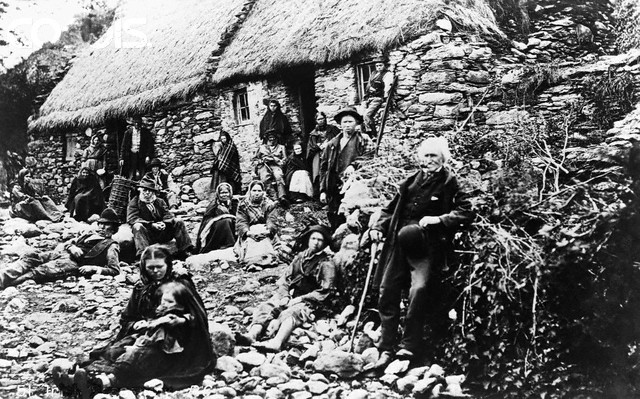

A) Irish as old immigrants – the Irish were a highly visible old immigration group, because they tended to be mainly Roman Catholic (and perceived as a threat to the freedoms of a profoundly Protestant—if avowedly secular—country), and because they immigrated in huge numbers.

1) Changes in landholding – although we traditionally think of the number one cause for Irish immigration as the Great Famine, Black ’47, Irish immigration in large numbers actually began years before the Famine. In fact, changes in landholding patterns throughout Europe were the primary cause for the immigration of peasants to the western hemisphere.

(a) Termination of serfdom – serfdom (a classification of station, of social order, similar to slavery) existed throughout Europe at the beginning of the modern era (for our purposes, 1600). Serfs were peasants who were tied to the land they worked for their lord (the owner of a manor). Serfs usually owed their lord a portion of the crop that they raised, and usually had to perform a fixed amount of labor for the lord on the manor, as well. Serfs were not completely propertyless, however; they usually owned a crude house, the adjoining land, and a small portion of plot that was worked in common. Serfdom was ended in England and the British Isles (including at this stage Ireland), in the 1600s; there were few serfs in France by the French Revolution in 1789. Serfdom did not completely disappear in Europe at this earlier time period, however; it existed in Prussian well into the 1800s, and Russian did not abolish serfdom until 1861. The termination of serfdom meant, however, that a large portion of the population in Europe was now free to roam around, and many peasants did so, seeking employment to supplement their subsistence from the land.

(b) Termination of the commons – a portion of a manor was common land, or the commons—land which all members of the community had rights to use. Use of the commons continued to exists in western Europe after serfdom ended, which allowed the practice of subdividing land among all of the male heirs in a family, since they could use the commons to hunt, gather peat for fires (there were very few trees left in Europe, particularly in England and Ireland, by this time, and most of the trees that were left the monarch claimed for military use), and graze livestock. With the growing importance of raising commercial livestock, the former lords of the manor (who remained the largest landholders), began seizing the commons; to keep the livestock of villagers from using the former commons area, large hedges were grown around the perimeter to keep other livestock out. These hedges can still be seen in England and Ireland, even though free range (similar to the commons idea) has returned in Ireland.

(c) Rise of primogeniture landholding – the amount of land to be divided became smaller, because of the practice of division among all male family members, and because much of the land was held be gentry class. This meant that individual landholdings got smaller, and had to be farmed more intensively—which became disastrous when the famine hit Europe.

2) Rise of manufacturing – as landholding was changing in Europe (particularly in England and Ireland), manufacturing and industrialization were beginning to take off in England and the United States.

(a) Manufacturing in England – the manufacturing of textiles in England—particularly in Liverpool and Manchester—as well as the manufacturing of iron and steel in Birmingham attracted workers from around the British Isles, who searched for ways to increase their incomes. Many agricultural workers and displaced farmers began to migrate to these developing industrial areas during lulls in the agricultural year to supplement their incomes; some stayed on permanently.

(b) Manufacturing in the United States – opportunities in manufacturing in the United States—as well as jobs constructing a transportation infrastructure (canals and railroads) attracted a great number of these displaced peasants and agricultural workers, particularly during the 1820s and 1830s.

(i) Because of the increased cost of migrating to the United States (as opposed, say, to Liverpool or Birmingham) meant that only immigrants with some means came to the United States—that is, they had some prior savings, or some skill that they hoped would transfer (many Irish immigrants had been cottagers in Ireland—that is, they worked as independent textile manufacturers. Most had to leave their looms behind, and upon arrival in the States found that most textile manufacturing was done in factories, anyway)

3) Black ’47 – the potato blight affected much of Europe, and was part of the cause of the increased migration from Germany, as well as Ireland.

(a) Reliance on the potato – because of the small amount of arable land available to most European (and especially Irish) farmers, they sought a crop that provided the greatest amount of calories per acre, which happened to be potatoes.

(b) The potato blight – the first year of the blight was 1845, devastating much of the crop that year; 1846 the blight was less worse, and seemed less threatening; 1847 it devastated most of the potato crop, as well as much of the population.

(c) Blight and immigration – the blight increased the urgency of immigration from Ireland, which was already occurring.

(i) Immigration to England – the poorest immigrants immigrated across the Irish Sea to England; because of their dire condition, many did not complete even this short journey.

(ii) Immigration to the United States – many Irish immigrants to the United States, while they arrived in the country destitute and often in ill health, were those who began the journey with the best chance of survival. Even so, about 10% died on the journey, a rate roughly comparable to slave ships.

B) Transportation technology

1) Sailing ships – the trip across the Atlantic took anywhere from three to six weeks, depending upon the weather and the port of departure. This length of time, and the conditions of travel in steerage, where most immigrants spent the trip, contributed to the mortality rate. The change of technology to screw-driven, steam-powered ships in the 1870s and 1880s had the double effect of decreasing the length of time the journey took, as well as dropping the price of the trip

C) The “Immigration Problem”—the assimilation of immigrant groups has caused concern among political elites in the United States since before there was a United States; Benjamin Franklin was suspicious of the people he called the “Dutch” in the area around Philadelphia (largely because of their loyalty to the Penn family, with whom Franklin was in near constant dispute with) is one of the early examples.

1) Local politics—new immigrant groups were viewed by political and economic elites as compliant tools of corrupt, big-city political “machines.” Immigrants could only make demands on these machines when they had votes to trade for services, however.

2) Hull House—established by Jane Addams and Ellen Starr in Chicago in 1889, in one of the poorest immigrant neighborhoods in the nation. Before Hull House residents provided political organization (and lots of publicity), residents in the neighborhood received few city services.

II) New Immigration

A) Transportation technology -- the change in technology allowed peasants and workers to move back and forth between Europe and the United States, which both the eastern and southern European immigrant, as well as those from northern and western Europe, took advantage of.

1) Screw-propeller steamships – the invention of the screw-propeller steamship cut down the length of travel from three to six weeks to one to three weeks, again dependent upon the port of departure (and arrival). This increase in speed allowed ships to make more trips; this led to the development of ships devoted to carrying passengers (to this point, the main income for a ship was cargo, rather than passengers), which allowed better accommodations for steerage passengers as well as cutting the cost of the trip to less than $10 one way.

2) Sojourners/Remigrants – there had always been sojourners (people who intended only to be temporary residents of a country—also referred to as remigrants), but the price drop for the trip, and the growing assurance that one would survive the trip in relative comfort, made the trip to the United States increasingly attractive to large numbers of working-class Europeans.

(a) Signaled a change in the nature of US immigration, because many of the people entering the country after 1870 did not intend to become permanent residents of the country, let alone become citizens.

(i) Increased resentment and angry reaction on the part of native Americans, which contributed to the renewed nativist sentiment in the country (leading eventually to legislation being passed in 1924 to restrict the numbers of immigrants allowed in the country each year.

(b) Attracted by high wages in US – the wages that a sojourner could obtain in US industry outpaced by far the wage they could command for agricultural and industrial work in Europe, and resulted in huge numbers of these workers, largely male, making their way to the United States.

(i) The labor movement, which should have worked to organize these new immigrants to keep them from lowering the wage rates for all workers, instead attempted to restrict the number of immigrants allowed into the country each year

(ii) Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) – at the instigation of labor in the West, particularly in California, but the entire labor movement eventually fell in line on this matter, including the Knights of Labor, which had practiced bi-racial unionism.

(iii) Because of immigrant interest in earning as much money as quickly as possible, most were uninterested in striking, or joining unions which often demanded union dues.

(i) Few immigrants in the 1870-1920 time period came with skills, so were unattractive to unions within the AFL (the dominate organization for labor during this time period—although the founder of the AFL, Samuel Gompers, was himself a Jewish immigrant from England.

B) Immigrant institutions

1) Church – many immigrants came from countries were Roman Catholicism was the dominant religion; the Church in Europe was dominated generally by the ethnic group that dominated within the country; in the United States, the RC Church was dominated by Irish and German clergy.

(a) Polish National Catholic Church – the response of a small part of the Polish population in the US was to establish their own church, which retained the practices of the RC Church except for recognition of the ecclesiastical authority.

(b) Conversion to Protestant sects – some immigrants converted to a Protestant sect, which caused consternation when they returned home to establish new churches.

2) Fraternal organizations – because of the high-risk jobs that immigrants tended to take (in return for what they thought were high wages), insurance became increasingly important (for burial, etc.)

3) Saloons – one of the avenues for upward mobility for immigrants was to open a saloon. This became a social gathering place for members of ethnic groups, a place where they could read newspapers, carry on conversations in their native tongues, receive and send mail, and bank. The saloon also served as a center from which to gather information about job openings, because the saloon owner was usually well connected.

C) 20th Century changes in immigration

1) Democratization of Europe – with the defeat of the Axis Powers in World War I, most monarchies on the Continent were done away with, and ethnic groups found themselves able to create their own governments; this not only tended to keep peasants home, but also drew back (initially) migrants already in the United States.

(a) Poland – had been a part of three different countries since the late 1700s, and was able to establish its own government (until 1939, that is)

(b) Czechoslovakia

(c) Yugoslavia

(d) Austria

(e) Hungary

2) Immigration restrictions – by 1924, when the euphoria for the new governments was wearing off, restrictions on immigration in the US became law, and took effect by 1927.

3) Economic depression – by the beginning of the 1930s, the worldwide economic depression ended employment opportunities in the United States.

III)Conclusion

No comments:

Post a Comment