A. Propaganda

1. Thomas Paine and Common Sense--perhaps the only author to approach the popularity of Paine’s pamphlet in modern times is J.K. Rowling (Common Sense sold about 150,000 copies in a country of less then 3 million people, including slaves who were kept largely illiterate--the equivalent sale today, with a population of 300 million, would be 15 million copies)—or the 18th century version of a viral video, since tens of thousands of more people read Common Sense than purchased a copy. Paine’s irreverent, vigorous prose captured the mood of the times, and was probably responsible for giving voice to a great deal of dissatisfaction.

B. Class conflict

1. Worcester County Mass.--farmers closed down the county court system to prevent creditors from using the courts to collect debts; this same action after the victory over the British provoked a different action from the men known to us as the Founding Fathers.

2. Hudson Valley New York--small farmers at this location decided to support the loyalist side, because of the obscene rents they had to pay to Patriot Patroon landholders.

3. The Revolution and Slavery--the rhetoric of freedom and rights resonated with many slaves--and many whites in the northern colonies, who began to question the morality of holding other humans in bondage

a) Many slaves in the north fought for their freedom--and the freedom of whites--in the militias and in the Continental navy.

b) In the colonies of the south, on the other hand, many slaves fled their masters in the hope of gaining freedom promised by the British government (Thos. Jefferson’s reaction to this was excised from the final edition of the Declaration of Independence.

II.) Tories (Loyalists) – who were they?

A) Wealthy conservatives – men with money who felt threatened by the rhetoric of republican theory and the rise of the common man. Wealth Tories tended to remain loyal because they were doing well financially, usually because of their trade with Great Britain, and did not want to see any changes that affected that. Not all wealthy men were Tories, however; men who made a substantial amount of money from the smuggling trade, and whose economic well-being was adversely effected by the vigorous enforcement of duties, chose to become Whigs, or Patriots.

B) Oppositional culture – while generally one would associate oppositional culture (that is, the culture in opposition to the prevailing culture) with the Patriot cause, many poor and middle class people chose to remain loyal to the British crown because those men with money who ruled over them were Patriots.

1) Local politics – depending upon the politics of the local ruling group, many of the “lower sort” did choose their political affiliation based upon their opposition to the politics of the local ruling elite.

(a) New York – many lower sort Tories believed that they would be rewarded by the British government, like those tenant farmers on the Hudson Valley estate of Robert Livingston, Jr., who believed that they were going to be rewarded with “Pay from the Time of the Junction and each 200 Acres of Land,” and therefore signed a “King’s Book” promising to fight on behalf of the Crown. Militias put down this apostasy from neighboring towns, with somewhere between three to six tenants being killed, and nearly a hundred seriously injured. This belief that the King would reward their loyalty certainly undermined the wealthy Tory position.

(b) New Castle County Delaware – a mob of Tory refugees mobbed a Whig constable from his home and forced him to be whipped by an African American – a rather potent symbol in a slave state like Delaware (indeed, in any of the colonies, since slavery was legal in all of the colonies).

C) Non-white loyalists

1) Irish Catholics – very few Catholics supported the American Revolution, not because they opposed democratic reforms (although that was the case with the Catholic clergy), but because they were not welcomed within revolutionary circles (Patriots tended to be extremely anti-Catholic, and believed that Catholics, because of their alleged allegiance to the Pope, were incapable of republican government. Even in Maryland, founded by and for Catholics, the few Catholic landowners left in that colony tended to by Tories. The fact that the few Irish Catholics in the United States tended not to be seen as “white” is a story for another time (briefly explain the concept of “race”).

a. As with many such broad, sweeping statement, there are exceptions that prove the rule, since the most prominent Roman Catholic in the United States during the Revolutionary period was Charles Carroll, who was in fact a Patriot, signatory of the Declaration of Independence, and later Senator from Maryland.

2) African Americans – not all African Americans sided with the Loyalists, but nearly all slaves south of Pennsylvania did so—because they were promised freedom by the British government in return for their allegiance.

(a) Lord Dunmore – the royal governor of Virginia, whose personality created a number of enemies among the members of the House of Burgesses; when that legislative body voted for independence from Great Britain, Dunmore retreated to a ship that sailed up and down the James River, creating havoc for planters who lived along the river. To create even more problems for Patriots in the colony, Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation, with which he “freed” all slaves in the colony who fled their masters and joined the British Army (point out the portion of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence that refers to this event).

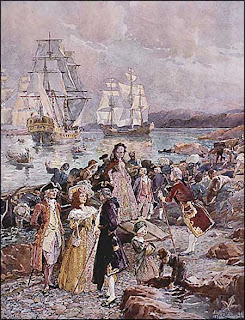

(b) New York City – was under British control for almost the entire duration of the war; it became a haven for runaway slaves during the Revolution, many of who fled with the British when they finally retreated from the city in 1783.

3) Native Americans – again, not all Native Americans sided with the British (most, indeed, attempted to remain neutral), but few native peoples saw it in their best interests to fight alongside the Patriots. Most of the battles that Native Americans were involved in occurred in the so-called “frontier” areas, which were scenes of constant battles between natives and Euro Americans, anyway.

IV) Patriots (Whigs) – like the Tories, Patriots could not be distinguished by occupation or social standing, although their decisions were often based upon economic decisions that they made in regard to their lives.

A) Wealthy “liberals” – people of wealth who had seen their economic successes threatened by this vigorous enforcement of tariffs generally sided with the Patriots.

B) Military militants – made up the core of the various state militias and the Continental Army. The majority of these men (and not a few women, who usually served a less than official capacity) served in these military units because of both an ideological commitment to the republican principles of the Revolution, and because they believed that these principles would serve their economic interests, as well.

1) “Summer Soldiers” – Thomas Paine’s rather derisive name for the various state militias, because they tended to fight in warm weather, when hardships were few—and after they had planted that year’s crops. The number of militiamen available to fight during any given period was difficult, a fact that exasperated the officers of the Continental Army.

(a) Philadelphia militia – is perhaps the epitome of both the strengths, and weaknesses, of the militias

(i) Committee of Privates – questioned the “rights” of the rich to rule over the poor; advocated that there be no distinction in the ranks, that poor militiamen and their families be provided for so that their service to their new country would not bring hardship to their families; the Committee of Privates was also the driving force behind the Pennsylvania constitution, which created a unicameral legislative body (no distinction in ranks) and a weak executive—this became the model for the national government created by the Articles of Confederation.

(ii) “Battle of Fort Wilson” – because the militia in Philadelphia was largely a political body (although they did see action when crossing the Delaware with Washington and in defending the city against British attack), the militia spent as much time agitating in the streets as they did in military maneuvers. The inflationary effects of war struck privates in the militia particularly hard, and the privates often took to the streets to protest against what they saw as profiteering by a few wealth merchants; one of these merchants, James Wilson, holed up in his house, where members of the militia found him, dragged him from his house, and threatened to tar and feather him; Wilson was saved by Joseph Reed, the president of Pennsylvania (at the head of the legislature), in a battle where five of the militiamen were killed and at least fourteen were wounded.

2) “Winter Soldiers” – the foots soldiers of the Continental Army, who suffered through most of the rigors of war, including two horrible winters, one near Morristown, New Jersey, and the other in Valley Forge, Virginia.

(a) Most of the foot soldiers in the Continental Army fought not for the ideology of the Revolution, but because of economic necessity. They were promised regular pay (something that they often times had to do without), and a bounty of land after serving a year or two in the army—a powerful incentive for the poor, who saw the way out of their condition access to cheap (or, in this case, “free”) land.

(b) Because the Continental Army was so ill supplied in the field, they were dependent upon their ability to “forage” for enough food and material to remain in the field; most of this foraging was done at the expense of farmers in the area where the Continental Army was encamped. Farmers were often given script as pay for the goods that the Army foraged from them; the fact that this script was often non-negotiable led to a great deal of resentment by those farmers so victimized, who saw their well-being threatened by a revolution that they might not support.

III) Why the Americans won – did the Americans “win” the war, or did the British forces lose?

A) Military prowess – did either side have this? The British forces were commanded by a succession of dandies, with little experience commanding an army in the field (particularly against an opponent which preferred to fight from behind rocks and trees in hunting shirts); yet the Continental Army itself only won a handful of battles (three of the largest in importance were the Battle of Saratoga, Cowpens, and the Battle of Yorktown, where the British Army was forced to surrender after a lengthy siege).

1) Defensive war – the Continental Army largely fought a defensive war, and used the fighting retreat to great effect

2) Lengthy supply lines – the British army, and its mercenaries, had to fight the war in hostile territory, an ocean away from its main base of supply. The British Army was only able to establish itself in the larger cities of the east coast; any other area that they briefly controlled was quickly taken back over by Patriot militias after the British Army pulled out.

B) Ideology – what part did ideology play in this war? Certainly, the foot soldiers had little ideological stake in the war; many fought as mercenaries (the Hessians, in particular, who were overrun early Christmas morning in Princeton after staying too long at the office Christmas party).

1) Declaration of Independence – how big a role did this document play in forming the ideology of the American Revolution?

I) Articles of Confederation – because of the belief that the government which governed the best governed least, the government that was created by this document created a weak central government, one that was reliant upon the states for support and the money with which to run it.

A) Economic problems – a series of economic problems in the post-war era undermined support for the Articles of Confederation.

1) Inflation – the Continental dollar traded against the Spanish dollar at the rate of 3 to 1 in 1777, 40 to 1 in 1779, and 146 to 1 in 1781, by which time the Congress had issued more than $190 million in dollars. The tremendous increase in prices led to a great outcry, which state and local governments responded to this crisis with attempts at wage and price controls.

(a) Perceptions that the problems were caused by hoarding, and often mobs in towns “called” upon merchants suspected of hoarding—or worse, of price gouging—to demand that they sell their merchandise at “fair” prices; those who refused often (but not all of the time), had their merchandise removed and sold by others at a “fair” price.

2) Deflation – in the years immediately after the Revolutionary War, the fact that the new United States had few manufacturing industries, and continued to export raw materials and import finished goods, meant that the trade deficit continued to grow with the US’s largest trading partner, Great Britain.

(a) Currency drain – in order to pay for goods imported from Great Britain, US merchants had to pay in gold or silver, which meant that the supply in the US decreased

(b) Public debt – the deflationary spiral occurred at a time when the United States had a huge public debt to pay off from the money the government borrowed to finance the war; this meant that the money which was borrowed was even more expensive to pay back than had been anticipated.

No comments:

Post a Comment